A fleece-reinforced liquid-applied membrane worked beautifully to seal the roof of 1 WTC. Penetrations, drains, and the base of the tower were detailed with the same system

On many jobs, the installer must deal with dozens of penetrations, extensive detailing at the transitions, and the sheer scale of tens of thousands of square feet. Often, heights and exposure also require careful planning to ensure the materials and workers remain safe.

Fortunately, many of these challenges can be overcome through state-of-the-art materials and careful craftsmanship.

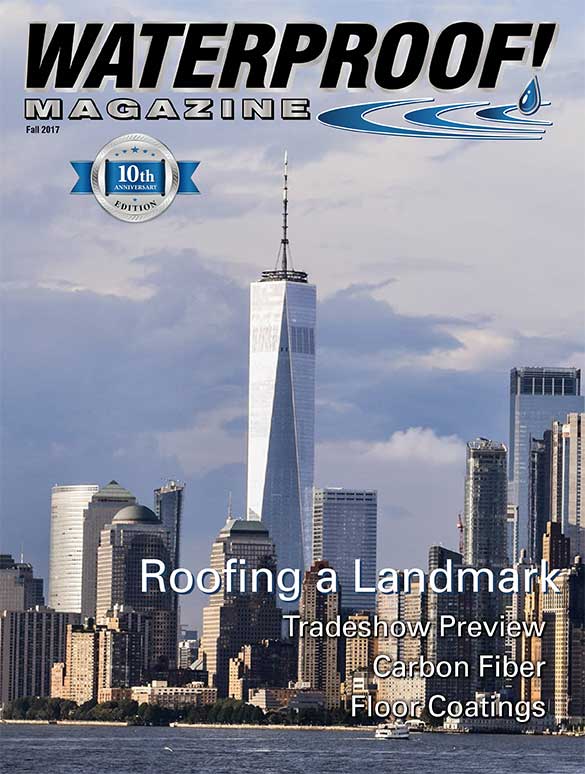

The Highest Roof in New York

One of the most prominent projects to be completed in recent years is the $3.9 billion One World Trade Center (1 WTC, formerly Freedom Tower) in New York City. The iconic landmark at the southern tip of Manhattan replaces the twin towers destroyed on 9/11, and finally opened in 2014 after nearly a decade of construction.

With most new construction, the building envelope—including the roof—is completed first. In this case, the main roof was one of the last structural items to be completed.

The Jobin Organization, Inc. of Farmingdale, NY, got the contract to install the roofing and waterproofing. Founded in 1968, they’ve become a powerhouse in the New York construction market in areas such as roofing, waterproofing, exterior restoration and construction management.

The challenges involved with roofing and waterproofing a high-rise are magnified with height. With an official height of 1,776 ft., this project is by far the tallest project built on U.S. soil in decades. Steve Guarino, general superintendent for Jobin, says the pressure was on to make sure the job was done right. “A billion eyes were watching,” he says.

The waterproofing story at 1 WTC really began more than 30 feet below ground level. Following the resolution of project design and financing issues, construction finally got underway in the spring of 2006. Ironworkers erected the steel at a fairly steady pace, and every 10th floor required temporary waterproofing with EPDM sheet and caulking until a new slab, 10 stories above, could be poured. Skyscraper cranes would lift bundles of steel and palettes of materials from the ground up or from one completed section to the next. Month after month, the arm would swing from the outside frame of the building, and deposit bundles stories above.

The Jobin crew waterproofed the roof perimeter and exposed steel at these levels as well as the top three floors of the main roof—floors 103 to 105—which are exposed to the elements.

The main roof is about 19,000 square feet, and Guarino estimates there were 300 or 400 penetrations on the main roof. That included the structure for the three cooling towers and the spire, as well as the everyday vent pipes, drains, conduits, plumbing and other piping. He says, “There were no areas bigger than about 10 ft. x 10 ft. without some penetration.”

A reinforced membrane system from Kemper System America was specified for the main roof and louvre areas on lower floors that are enclosed on three sides. It’s a liquid-applied resin membrane system reinforced with fleece and can conform around any shape. Penetrations, drains, curbs and perimeters are sealed with the same components and then overlapped by the membrane in the larger expanse to provide durable waterproofing protection.

Jobin has completed dozens of projects with this cold-fluid-applied reinforced membrane system. “One of the primary reasons we won the bid was [that Kemperol would work with] all the exposed steel and many penetrations,” Guarino says. He ran a crew of 15 to 20 workers on the job. “There were so many configurations that needed waterproofing,” he says, “curbs, drains, HVAC, beams, nuts and bolts, and around the base of the spire. There was so much steel, sometimes we were ‘bumping heads’ with our hardhats.”

The work on the main roof membrane began in mid-June 2014 and was completed in mid-October. At nearly one-third of a mile high, the weather at the worksite could be quite different than at ground level. “A lot of times when it was a cloudy day on the ground, it could be foggy. Or if it was foggy on the ground, it could be raining when we got to the top,” he says. “But the heat was not too bad, and there was no sweltering hot weather.”

For the main roof, they first installed insulation and pre-primed cement board, adhered with beads of foam adhesive. The cement board was staggered so the joints never aligned with those of the foam board beneath, then sealed the seams with beads of polyurethane sealant and four-inch wide strips of Kemperol.

One obvious challenge in waterproofing a high-rise is simply getting materials to the roof, and this job was no different. “By the time we got to the roof, the outside hoist had been taken down, which might have saved a little time,” Guarino said. ”But with [this] system, there’s no heavy equipment, so we were OK. The heaviest tool we used was a hand mixer for the resin.” The trek to the 105th floor could take up to two hours because of all the trades on site. Often, the crew would bring materials up via freight elevators on the weekends in order to have the required materials ready to go.

“We would take materials from the loading dock to the main floor elevators, up to [floor] 102, and then transfer to 105. The insulation and cement board were loaded on 4 ft. x 4 ft. skids and stored on floor 104 during the job.”

The manufacturer had a rep on site at least once a week to inspect and advise on the job. In addition, a building envelope consultant photographed progress daily to provide feedback to the A/E/C management team. There were conversations with the management consultants every morning to make sure everything was running smoothly, Guarino said. The thickness of the roof slab often meant there was no cell phone service available, so urgent messages were often relayed via walkie-talkie to a lower floor, where workers could get reception.

“The biggest challenge was coordination on the job site,” Guarino says. “There were a lot of trades there at the same time.”

Protecting The Priceless

The Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. houses some of the most precious collections in the world. Since 1983, those collections not on display in the museum proper are stored in the state-of-the-art Museum Support Center (MSC) about seven miles away in Maryland.

The MSC holds more than 50 million items, ranging from Antarctic meteorites to dinosaur fossils and preserved giant squid. The complex is laid out in a unique architectural zig-zag design and is outfitted with the latest technologies to provide optimal storage conditions and security.

A fleece-reinforced roof was also used to protect the off-display collections at the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center.

By 2017, it was time to update the roof. That required a partial tear-off, with new roofing materials installed on 660,000 square feet. For a structure like MSC, confidence in the longevity and performance of a roofing system is a necessity. Like the 1 WTC job, MSC building managers chose a cold-fluid-applied reinforced membrane system, this time using a system from Soprema.

After the tear-off, crews began by installing two layers of rigid polyisocyanurate thermal insulation totaling six inches thick. These were adhered to the existing membrane using two-part polyurethane adhesive and helped improve the thermal efficiency of the building—a necessity for the MSC’s rigid climate control.

More than 50 million priceless items depend on the roofing system to perform as intended.

The rigid insulation was covered with a ¼” semi-rigid, asphalt-saturated fiberglass board. It provides superior compressive strength and is used in some of the highest wind- and fire-rated roof assemblies. Then the actual roofing membrane could be applied. Soprema’s Alsan is a polyester-reinforced, liquid-applied roof membrane using polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and polymethacrylate (PMA) based resins that offer rapid set times and minimal maintenance.

The result was a flexible, seamless, watertight, puncture-resistant membrane that will help ensure that the MSC is able to successfully house priceless collections for future generations to come.

Liquid-Applied Roofing Membranes

Both projects featured in the adjacent story use reinforced liquid-applied monolithic membrane systems.

Kemper claims to have developed the first cold liquid-applied, fully reinforced waterproofing membrane in the late 1950s. Today, these systems are available from a dozen leading manufacturers, and have decades of proven performance in every conceivable application.

As a roofing system, it straddles the line between roof coating and roof membrane. It’s applied as a liquid—typically composed of a high-tech polymeric resin such as urethane or rubber polymer—via roller, brush, or one- and two-component spray guns.

Frequently, a non-woven fabric, fleece or mesh is added for reinforcement, either across the entire roof, or only in select areas, depending on the application. The liquid cures to form a tough, seamless, rubber-like membrane.

Liquid-applied systems provide a monolithic, self-flashing membrane that is easy to apply and conforms to any shape. It’s ideal for waterproofing applications where use of a sheet membrane is difficult, due to corners, penetrations, or other factors. It’s especially popular when the job involves confined urban space, numerous roof penetrations or restricted use of hot asphalt or heat welding. These systems can be applied in temperatures that are too low for other systems to be installed.

As illustrated in the accompanying story, these systems have been used for roof restorations and new construction. They can be installed over most existing roof types, eliminating the need for tear-offs or installation of cover boards. There are no hot kettles, no expensive installation equipment, and no special seaming devices. On new installations, they work especially well with concrete and steel substrates.

Once installed, periodic maintenance coatings (along with a regular schedule of cleaning) will preserve the roof with no additional steps needed.

Reflective white colors are popular as “cool roofs.” Others are covered with a reflective coating, a cap sheet for a cool roof option or granules for an aesthetically pleasing surface.

For additional information, see “Fluid-Applied Roof Coatings” in the Fall 2015 issue at www.waterproofmag.com.

Fall 2017 Back Issue

$4.95

Floor Coatings as Waterproofing

AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | Digital Download Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|