By Clark Ricks

In the last issue of this magazine, we addressed fixing failing poured wall foundations. Part II, printed below, offers solutions for fixing bowed, cracked, or leaking foundations made from concrete block.

–The Editor

In many parts of the country, foundations and basement walls are constructed with concrete masonry units (CMU), also called concrete block or cinder block.

CMU foundations offer a number of advantages. They’re more versatile than poured concrete, and easier to alter—both during construction and in the future. They have plenty of strength, and in most areas the installed price is comparable. In some regions, such as the Upper Midwest, nearly 80% of basements have CMU walls.

CMU foundations crack for many of the same reason poured walls do: differential settling, backfilling too soon, expansive soils, tree roots, hydrostatic pressure, etc. Regardless of why they crack, a number of solutions exist.

Identify the Problem

CMU walls nearly always crack along the mortar joints. The pattern of these cracks can reveal much about the underlying cause of the problem.

“The first step in any basement wall repair project is figuring out the cause of the problem,” says Bob Thompson, P.E. co-founder of The Reinforcer. “A big part of that is knowing what to look for and how to read a crack.”

Long horizontal cracks—usually a single horizontal crack in the center two-thirds of the wall—indicates pressure outside the building pushing the wall inward. This bowing can be caused by hydrostatic pressure (poor drainage), or expansive soils.

So called “frost line” cracks look similar and form at the height of the exterior frost line.

Bowing is extremely common. “Most older block walls are bowed about a quarter inch in the middle,” says Andre LaCroix, president of StablWall Wall Bracing. He notes that these cracks are usually the easiest ones to fix.

Stair-step cracks, which extend diagonally across the wall in stair-step pattern, are much more serious. They usually indicate one part of the home has settled faster than another, which can cause major structural damage. These cracks usually start at a weak point in the wall, like a window or door opening, and run the entire height of the wall. A stair-step crack wider at the top than the bottom is a typical sign of settling.

LaCroix cautions that it’s wise to get a professional opinion on the cause of cracking before making any decisions.

Thompson gives this example: “When a crack caused by bowing gets within two to three feet of a corner, it will begin stair-stepping to the corners of the room. It looks like a settlement crack, but it’s really just a bowing problem,” he says.

Repair Options

If experts determine the cracking is caused by settling soils, these range from simply filling the cracks with epoxy or foam to a complete rebuild of the wall. In many cases, underpinning is also an option. This complex topic is explained in Part I of this story. (See Fixing Failing Poured Wall Foundations in the Spring ‘08 issue, pp. 10-14). Basically, steel or concrete piers are driven or screwed into the soil, then attached to the house to eliminate settling.

For bowed walls, traditional solutions involve steel beams or wall anchors. But in the past few years, new technologies have been developed that make CMU foundation repair less invasive, less expensive, and less visible than ever before.

Steel Beams: Long considered the “standard fix” for bowed walls, this method involves anchoring a steel I-beam to the top and bottom of the wall every four or five feet to stop the bowing.

Some contractors will bolt the bottom of the beam to the floor. Others will actually remove a small portion of the concrete slab, place the beams on the footer, and then pour new concrete around the steel to anchor it into place.

Steel I-Beams, set every four to five feet along the wall, are the traditional solution to fixing bowing.

The top of the beam is braced off the joists.

One intriguing variation of this system is the Gorilla Brace, which claims to “not only repair bowing walls, but will actually push them back again.” Nationwide Reinforcing markets “The Force” which works on a similar principle.

Braced off of three floor joists (instead of just one), the Gorilla Brace uses a powerful spring that exerts almost 1000 pounds of lateral force. The continual pressure eventually will push the wall back into its original position.

The website notes that using “a 6-inch trenching machine or a narrow back hoe outside of the moving wall… allows the buckling walls to be pushed back by the installed wall brace… the same day.”

The steel beam method is one of the oldest and most reliable methods. It solves a wide variety of problems, and is sometimes the most cost-effective solution. The work is done inside the basement, so it can be performed year ‘round, and in most cases, there is no digging up the yard.

On the other hand, homeowners have to deal with steel beams being carted through their home. They lose four to six inches of interior floor space for each wall that gets braced. And during construction, they have to deal with the inconvenience of jackhammer noise, buckets of concrete rubble, and dust.

Wall Anchors: For serious bows in the middle of the wall, anchors are extremely effective. An “earth anchor” is buried outside the home, 10 to 15 feet away from the bowed wall. Then a large threaded rod, often an inch or more in diameter, is threaded through the wall and attached permanently to the anchor. A “wall plate,” usually about two feet square, is attached to the interior end of the rod, and fastened into place with a nut. The nut is then tightened until the bowing has been minimized.

Wall anchors require significant excavation. Metal plates on the interior (at right) keep the wall from bowing further.

This method is effective, and it doesn’t reduce room size like steel beams do. However, it does have drawbacks. It requires significant excavation around the property, and assumes the lot is big enough to place the anchors. Additionally, the wall plates have to remain exposed for the life of the building so they can be periodically tightened. This reduces basement finishing options rather dramatically, since access doors would have to be placed every six feet or so. Also, additional cracks may form around the wall plate if it’s tightened too much.

Anchors were used to stabilize this bowing CMU wall. Note the crack that runs the length of the wall just above the anchors.

Carbon Fiber Straps: The newest method for fighting wall bowing is to use high-tech carbon fiber. Systems such as StablWall, The Reinforcer, and Fortress Stabilization harness the incredible strength of carbon fiber to stop wall bowing permanently. Best of all, the systems are easy-to-install, non-invasive, reasonably priced, and nearly invisible when complete.

“We wanted to come up with a carbon fiber product that would work in 95% of basements,” says LaCroix, at StablWall. His solution, a 2-foot by 5-foot sheet of carbon fiber epoxied to the wall, works on CMU, poured concrete, and even brick and clay tile.

Other systems consist of carbon fiber straps about 4 inches wide that run the height of the room. All are about 1/8 inch thick, about the same thickness as a coin.

The wall above (top) shows classic signs of bowing. After the cracks are filled (middle) and the carbon fiber is in place, repairs are finished. After painting (bottom) the repair is practically unnoticeable.

The key to all these systems is the incredible tensile strength of carbon fiber. While steel can resist 30,000 to 40,000 lbs. of tension, carbon fiber can withstand 8 to 10 times that much pressure.

When a block wall bows, the exterior face of the wall is compressed and the interior side stretches; that’s what causes cracking. Carbon fiber products keep the inside face of the wall from stretching, and if it won’t stretch, the wall can’t bow.

The fibers, however, have very little compressive or sheer strength, so the fibers must run perpendicular to the crack, and the crack must be filled to keep it from closing.

All three of the carbon fiber systems mentioned above can be installed in less than a day, and installation methods are fairly similar.

After determining the location of the reinforcing, and marking it on the wall, the next step is to grind off any paint, dirt, or other residue in the area the strips will be applied.

“Then we’ll come in and using an epoxy–based crack filler, fill all the cracks and mortar joints,” says LaCroix. “Basically, we want to make it as smooth as possible.”

After the cracks are filled, a primer coat of epoxy is applied to the wall and to the back of the carbon fiber product, which is carefully attached to the wall.

With The Reinforcer and Fortress, that’s all that’s needed. StablWall requires a second coat of epoxy to ensure good adhesion.

“As a material, it’s more expensive that steel beams,” admits LaCroix, “but factoring in the lower cost of labor, the lower overall cost of tools and manpower hours, and demand for the product,” it means more profit for the contractor at a similar price for the homeowner. You don’t need jackhammers or backhoes. There’s no crew hauling out buckets of concrete. You can work out of a pick-up.”

He also notes that carbon fiber is in contact with the entire height of the wall, where a steel beam or anchor would contact the wall for a limited distance

Thompson, at Nationwide Reinforcing, adds, “Instead of a 4- to 6-inch I-beam, this is the thickness of a dime. Aesthetically, your options are still virtually unlimited. You can paint it, furr it out, or just leave it the way it is. I hear from customers, if they go to a basement and see beams, they think there’s a problem. If they see carbon fiber, it’s less of a detriment.”

Still, carbon fiber does have limitations.

“If we see a wall that has bowed in excess of 2 inches, or sheer from block to block, it’s not suitable for carbon fiber,” says Thomson. “It’s not designed to straighten walls, or withstand sheer loads, or stop settlement.”

“Settling walls need to be fixed first,” agrees LaCroix. “Get a structural engineer to come in to analyze the situation. You may have to pier it to fix the problem.”

“We still do steel beams every once in a while,” he continues. “If the wall is tilted in from sill plate, or kicked in from the footer, we’ll use steel or recommend a complete rebuild of the wall, depending on the severity.

In extreme cases a complete rebuild of the foundation may be necessary. Luckily nearly all foundation problems can be solved with other methods.

Waterproofing

“If they have a water issue, they’ll have to address that completely separately from the reinforcement,” notes Thompson. None of the solutions mentioned above—beams, anchors, and carbon fiber—is a waterproofing product.

The challenge with block walls is that unlike poured concrete, CMU have a hollow core that is nearly impossible to seal entirely.

The best approach is from the outside.

If outside excavation is not a possibility, one option may be to install an interior drain tile, like Boccia’s Hollow-Kick Molding, to deal with the moisture.

Opportunities

For waterproofing contractors, adding structural repair capabilities to their business may increase profits and marketability.

Doug Klein, owner of Klein Basements in Erie, Pa., is one example.

The Erie Metropolitan Housing Authority owned nearly 100 houses with bowed foundation walls, all of which had to be stabilized in order to render the homes safe.

Klein proposed to fix the walls using the carbon-fiber based Reinforcer. Although it took more than a year before the bids were awarded, Klein says it was well worth the wait.

“The Housing Authority job (approximately 10,000 feet of Reinforcer) was a huge boom to our business,” he writes. “This product is one of the most profitable facets of our business… It’s great that there is no heavy, expensive equipment needed, thus, no costly breakdowns. Customers love it because it is so unobtrusive, and best of all it works, plain and simple.”

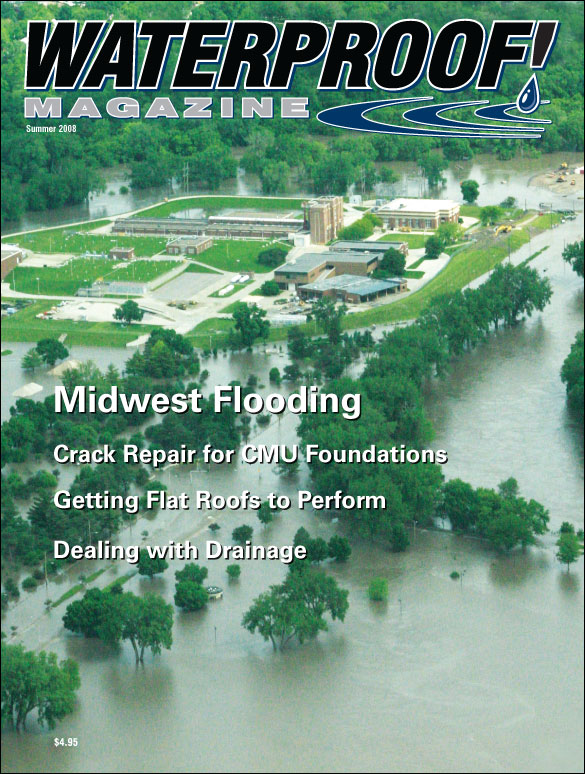

Summer 2008 Back Issue

$4.95

Midwest Flooding

Dealing with Drainage

Crack Repair for CMU Foundations

Getting Flat Roofs to Perform

AVAILABLE AS A PDF DOWNLOAD ONLY

Description

Description

Midwest Flooding

By Melissa Morton

Torrential rainfall in the upper Midwest has flooded hundreds of square miles along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Waterproofers are helping out as much as they can.

Dealing with Drainage

By Dan Calabrese

Every building needs a drainage system. This involves everything from properly sloping the lot to ensuring drain tiles and sump pumps are adequate.

Crack Repair for CMU Foundations

By Clark Ricks

Concrete block, or CMU is commonly used for basement walls in much of the country. Modern materials have created new options for repairing the cracks that inevitably appear.

Getting Flat Roofs to Perform

By Dan Calabrese

Standard in commercial construction, flat roofs are also common for residential work in some regions. The key to performance is proper installation, quality materials and a slight pitch.

Additional Info

Additional information

| Magazine Format | PDF Downloadable Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

|---|

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.