By Joel Lozon

If you are in the market for a new roof, then you’ve likely already realized that there are a lot of choices to make.

With so many choices, though, some leave the decisions to their roofing contractor. We just let them tell us what we should do. If you are blessed with the financial wherewithal to build your own building, then maybe you just let your architect make the call. Whether it’s your roofing contractor or your architect making your roofing decisions, either way may be ‘good enough.’ But it’s your money. So it only makes sense to educate yourself about the matter.

At the very least, arming yourself with the right knowledge—even a cursory amount—will give you the opportunity to ask pertinent questions. Then you can decide for yourself if the answers you receive satisfy you. You are potentially spending thousands of dollars on your roof. Making sure you’re getting the most out of your hard-earned dollars is just a sensible thing to do.

In two parts, I’ll attempt to answer the following questions in simple, straightforward language:

- What do all the letters mean?

- What are the potential pros and cons for each product?

- What’s the best choice for you?

We’ll look specifically at TPO, EPDM, and PVC, and attempt to discern the basic differences between the three systems. The first part of the article, which you’re reading right now, will look at TPO and PVC. The second part, which will publish in Waterproof! Magazine’s spring 2021 issue, will look at EPDM. That article will also wrap up with a comparison of the three products and information for you on how to make the best choice between the three.

Before getting into our article, bear in mind that the best product in the world will still fail if improperly installed. Success is almost always a collaboration of (1) a quality product installed by a (2) quality roofing contractor. If you remove one part from that equation it is generally unreasonable to expect that you will get what you paid for. Remove both from the equation? Well, I’m sure you can do the math.

I’ll also provide you with my expert opinion about the subject and give you another possible solution to your roofing problems. Keep in mind, too, that this is an opinion article. It is your responsibility to research your own specific circumstances thoroughly before making a decision on the best course of action for your roof. But I hope what is offered herein will help in that effort. So, let’s get to it . . .

What Do All Those Letters Mean?

The term TPO stands for Thermoplastic Polyolefin. Believe it or not, TPO is actually in a broad family of rubber roofing materials. TPO is a blend of polypropylene and ethylene-propylene rubber.

EPDM stands for Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer. It is a synthetic rubber derived from oil and natural gas (ethylene propylene). When the ethylene propylene is combined with diene (an unsaturated hydrocarbon alkene containing two carbon-to-carbon double bonds), the flexible EPDM membrane is created.

The term PVC stands for Polyvinyl Chloride. PVC materials are produced by a chemical reaction, known as polymerization. (Polymers are a natural or synthetic compound that consist of large molecules made of many chemically-bonded smaller molecules, known as monomers.) PVC is produced by the gaseous reaction of ethylene with oxygen and hydrochloric acid.

Now, if that wasn’t tedious and boring enough, there are several other roofing acronyms out there. For example, there’s CSPE, which stands for Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene; PIP for Polyisobutylene; and KEE for Ketone Ethylene Ester.

Holy cow, Batman! Do you really need to know all this stuff? No. But it is good to at least know that these letters mean something—that there is a chemically designed manufacturing process to these different roofing membranes. I’m only covering TPO, EPDM, and PVC because, frankly, they are the most commonly used products in the roofing industry today. They are probably what you are going to encounter most often.

With all the minutia out of the way, what you really need to know is, “What will work best for my roof?” Let’s tackle that next by trying to differentiate these roofing products in practical terms.

The Basic Differences

TPO

TPO is probably the most widely used roofing product in the market today for two very good reasons: (1) it’s relatively cheap and (2) because it’s white. Cheap doesn’t always make something better, though. In fact, that is seldom the case. And being white isn’t really anything special, not anymore anyway. Even EPDM, which is naturally a black membrane, is also available with a white laminated top. So is there anything about TPO that makes it a viable option for your roof? Absolutely!

Well, not really. I was just kidding. Over the years TPO manufacturers have revised and re-revised their proprietary formulations simply to get it to work. TPO—as it is currently formulated—does not have a long track record. That track record is also not very compelling. TPO is known to shrink and pull away from seams and curbs. That was one of many reasons for the constant reformulations of the product in the first place. Unfortunately, that problem hasn’t completely gone away yet. However, by the time you read this article, it’s possible some of those issues have been more adequately addressed. But knowing it is a potential problem will give you some additional insight so you can ask the right questions.

For example, there was an interesting article that appeared in Perspectives magazine, Volume 66, in May 2010 (benchmark-inc.com). The roofing consultants of Benchmark Inc. did an extensive hands-on study of TPO. Here’s what author Jeff Evans, RRC, had to say:

“Our investigations of our clients’ roofs continue to identify issues with some TPO membranes: splitting and crazing along rows of fasteners, accelerated aging along walkpads, polymer erosion to the point of exposing scrim reinforcement; enough issues for us to have concerns.”

That wasn’t even the funniest part. Yes, I said “funny.” When most people decide on a TPO roof, they often do so based on price alone. But a cheap roof is often . . . well, a cheap roof. Makes you wonder if they would have decided differently if they really knew what they were getting. So what are you getting with a TPO roof? Here’s the funny part:

“The MRCA T&R [the Midwest Roofing Contractors Association] committee recently released an “Advisory on TPO”, noting TPO’s potential susceptibility to deterioration from exposure to high heat and / or UV (solar) loads. Heat and reflected / focused sunlight are the primary concern in this advisory.”

C’mon, man? You’re kidding me, right? TPO is still not formulated properly to be able to handle sunlight? Hmmm. Not a particularly good quality for a roof, wouldn’t you say? See why it’s so funny? At the time of publishing this article, the advisory could still be found online on the Midwest Roofing Contractors Association’s website. (This article originally published December 2016, and the advisory is no longer online).

For fairness’ sake, Firestone (manufacturers of EPDM and TPO membranes) responded to the MRCA advisory as follows:

“Not all TPO products are the same. Other TPO roofing manufacturers may alter their formulations and experience issues with high solar and temperature exposure. This is not the case with Firestone.”

Benchmark responded to that response by stating the following:

“Firestone’s comment that “not all TPO products are the same,” and their statement that other TPO manufacturers might have “issues with high solar and temperature exposure” are at the heart of the issue for Benchmark. Clearly, there have been issues with TPO formulations. Who has it right? Does anyone?”

Does anyone? Good question. That article contained a lot more information about problems with TPO membranes; problems that have been around since its inception and continue to be addressed and re-addressed. So just because TPO is cheap and white doesn’t mean it would be a good option for you. Maybe it would be. After all, since this article was first published, a lot could have changed. But I’ll leave that for you to decide. I’m just here to present the information.

The TPO membrane can be mechanically attached (screwed) or fully-adhered (glued). (See Ballast Footnote on page 23) When it comes to the seams and the detail work, the membrane can be glued or heat-welded. The materials of the TPO membrane, however, make it a difficult material to heat-weld correctly. Though some TPO membranes have at least some pliability, others are nearly board-like in their rigidity.

A key component of a TPO membrane is its laminated nature. The material that you see on top is not the same material you see on the bottom. Often the top is white and the bottom is gray. This is because it is not the same material through and through. A wearing surface is provided on top and filler material is provided on the bottom. It’s kind of like a hot dog—there’s probably something good in there somewhere, but I wouldn’t want to eat it. Usually when you laminate something, it serves to create an added point of weakness. Fiber reinforcement is added to a TPO membrane that does make it stronger and more durable. But that sometimes comes at the expense of added rigidity, which makes it harder to work with during the installation process.

TPO is a roll good system, meaning that it comes in relatively small rolls. The rolls average about 8 feet wide by 50 or 100 feet long. Other sizes are available, but they are still relatively small. This means that there are a tremendous number of seams created during the installation process. Seams are the weakest part of any roofing system. The more seams that have to be field-welded or glued allow for more human error. More human error means a generally weakened roofing product throughout.

The primary thickness of a TPO membrane is 60 mils, with 45 mils still frequently used. There are also 72-, 80-, and 90-mil membranes available. (A mil is 0.001 of an inch; 45 mils equal 0.045 inches). Why such a wide range? In large part it is because many believe that “thicker is always better,” and manufacturers often cater to that belief. But thicker is not always better, especially when the thickness is designed to mask the inherent weakness of the product.

It’s like putting perfume on a pig. It may “smell” better, but it’s still just a pig. I’m not saying that TPO is a pig; that would be silly. I like pigs. But let me ask you, which is of higher quality: an 8-track tape, a vinyl record, or a CD? Obviously, a CD is the product with the highest quality, exponentially so. (Of course, that analogy only works for those of you that still remember CDs.) But CDs are also significantly thinner/smaller than their predecessors. And as technology improves—as engineering of a product becomes more refined—you typically get better quality at a smaller size. (For example, the same comparison to CDs could be made to digital media. Digital media is even “smaller” by comparison but is still of higher quality to that of CDs. Thicker is not always better.)

The right roofing material should be long-lasting, not deteriorate under UV conditions, and of course, protect the building from moisture.

Has anyone seen how thin big screen TVs are now? With the thicker-is-better mentality, we should all be buying the 4-foot deep LCD TVs, right? The fact is, with some things thinner is better and often indicates higher quality. Furthermore, making a roofing membrane thicker also makes it heavier, which makes it more expensive to ship. They are also much harder to properly seam in the field.

The good thing about TPO is that it does have a reasonably high resistance to animal fats, some hydrocarbons and vegetable oils, and microbial growth. And as I mentioned before, it is cheap. It is typically the cheapest of the three main roofing membranes mentioned in this article. Don’t get me wrong, it has its place. But you get what you pay for, and I’m not here to promote one over the other. It is what it is. But millions of square feet of TPO membrane are already installed with millions more to come. This product is not going away, so you need to be able to identify if quality, durability, warranty coverage, or cost is your main concern.

PVC

When it comes to PVC, most people probably first think of those hard irrigation or drainage pipes. While it is true that PVC is a relatively hard substance, the PVC that is used for roofing material has the benefit of plasticizers, which are added to make the membrane more pliable. Most PVC membranes are mechanically attached, though fully adhered or even ballasted PVC roofing systems are still occasionally found. What is almost universal, though, is that the PVC membranes are heat-welded at the seams. This creates a monolithic structure that is very durable and able to withstand the constant expansion and contraction of the building structure throughout the day, throughout its life. A properly heat-welded seam is a much better seam than a glued or taped seam. And the reason why PVC membranes are most often heat-welded at the seams is because of the strength, durability, and stability of the material itself which is unlike TPO, which can be very difficult to heat-weld properly because of the inferior quality of the membrane.

Thermoplastic membranes like PVC offer many benefits, including long-term weathering resistance, cold temperature flexibility, tear resistance, puncture resistance, chemical resistance and heat-seaming capability.

Though the PVC membrane has excellent puncture and heat resistant qualities, it is absolutely incompatible with asphalt-based products. So any time a PVC roof is to be installed in such a way as to come into contact with any asphaltic product, separator sheets must be installed to keep the PVC from directly contacting the asphalt.

PVC is relatively light and can be purchased in milages between 36 and 90 mils. However, the standard PVC roofing membrane is about 50 mils. Though the primary color of a PVC roofing membrane is white, it can come in a variety of colors and hues. It also has excellent resistance to bacterial growth, animal fats, as well as plant root penetrations.

Though PVC is usually a roll good system (meaning, it is ordered in 5- to 12-foot wide by 50- to 100-foot long rolls), it is not the nightmare that TPO is. As mentioned before, PVC seams are usually heat-welded. And because of the structural integrity of the membrane, this heat-welding can go relatively quickly and with a much better result than that of TPO.

PVC is a relatively hard substance, but plasticizers make it pliable enough to become a membrane. Most PVC membranes are mechanically attached, though fully adhered or even ballasted PVC roofing systems are still occasionally found.

However, it is important to note that there are PVC roof system manufacturers out there that actually custom prefabricate the membrane. This means that your roof is measured, including your curbs, walls, penetrations, etc., and then the roof is custom-designed to fit those dimensions. Such a methodology allows for all the benefits of larger sheet sizes as seen with EPDM, but with the added benefit of prefabricated curbs, walls, and penetrations. Your new roof is designed specifically for the size and constraints of real-world existing conditions.

This prefabrication process can also eliminate up to 85% of all the field seams. As you may recall, seams are the weakest link in any roofing system. By having about 85% of those seams already completed by the manufacturer in their quality-controlled environment, your roof is going to be significantly enhanced. But as stated before, a quality product is only half the equation to getting a good roof. The other half is a quality installation by a quality roofing contractor. So be very diligent in choosing your roofing contractor.

Another innovation that is gaining in popularity is induction welding of TPO and PVC thermoplastic membranes. A PVC application is shown here.

While most other roofing products can come in either reinforced or non-reinforced material, PVC is often reinforced right out of the box. Reinforcement typically indicates a polyester scrim, mat, or fabric mesh that is inserted into the material, like rod iron is used to reinforce roads or concrete walls. While some manufacturers’ reinforcement may be better than others, it’s good to know that there is a little more structural integrity from the get-go with a PVC roofing membrane. This reinforcement, which translates to quality, is one of the reasons why PVC is a little more expensive than TPO, though it is still competitively priced against EPDM. If overall quality is the criterion used to decide what your next roofing system would be, then a quality PVC product should be seriously considered.

This opinion article was reprinted and slightly changed from the original and published in two parts with permission from its author, Joel Lozon, who is an independent sales representative for RTN Roofing Systems. RTN Roofing Systems are the flat roof experts with offices in Colorado and Florida, and specialize in single-ply and roof restoration solutions for commercial and industrial facilities. Visit RTN Roofing online by going to www.RTNroofing.com or by contacting them at (970) 593-1100. For sales questions, please direct your inquiries to sales@rtnroofing.com.

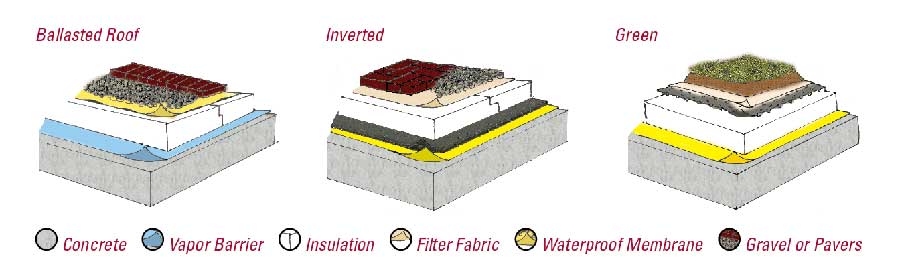

Ballast Footnote

Besides mechanical and fully adhered attachments, TPO, EPDM, and PVC can also be ballasted. This is when the roof membrane is held in place by aggregate. In a ballasted roofing system, the aggregate is usually stones at least an inch in diameter and applied heavily throughout the roof. In fact, the weight for a ballasted roof can range from about 15 pounds per square foot (psf) to about 25 psf. The minimum allowed by code is usually about 10 psf. That is very heavy. Increase that with snow loads, water loads (due to improper or clogged drainage systems), etc. and you can have a real problem.

Ballasted roofs are still out there and are still being specified, but I don’t know why. It is a dying breed, however. Many specifications that would have normally called for ballast went to mechanically attached, fully adhered, or vegetative (using plant life to hold the roof in place). Another variation of ballasted roofs that has gained some momentum is the use of concrete pavers. Though they can be installed in a more uniformly consistent manner and typically at a slightly lighter overall weight than its rock counterpart, you still get the same negatives with a paver system as you do with a rock ballast roof. Besides the excessive weight of a ballasted roof, another major downside is repair and maintenance. If your roof springs a leak, how do you know where it’s coming from? How can you get to it to repair it? Those rocks (or pavers) are very difficult to move around as you are investigating leaks. They’re heavy—collectively anyway—and they mask the condition of the roof. I like to call a ballasted roof the nuisance roofing system. It’s very easy to put on, but very difficult to do anything with it after installation day. My advice: Stay away from ballast if at all possible.

So why use ballast? Think about it for a moment: If you could get away with putting a cheap roofing membrane on your building and then “protecting” and “holding” it in place with several truckloads of rocks or pavers, wouldn’t that be the cat’s meow? It’s cheap. There’s no other way around it. You get little of the energy benefits of a white roof, you add significant weight to a building’s structure, and you create a nearly impossible repair scenario when the roof does spring a leak. Though we often encounter them when investigating leaks and doing reroofs/replacements, we stay away from the installation of ballasted roofs. They are typically not cost effective in the long run and are often more trouble than they are worth. When there are viable alternatives out there, there is usually no reason for a ballasted roof.

Winter 2021 Back Issue

$4.95 – $5.95

Waterproofing Basement Floor Slabs and Walls

Great Work, Wrong Project

History of Drain Tiles

Which System Is Better – TPO, EPDM, or PVC?

Making the Most of Digital Events

Becoming a More Digital Friendly Business

Description

Description

Waterproofing Basement Floor Slabs and Walls

By Vanessa Salvia

Waterproofing a basement or crawlspace depends on the site conditions, such as whether it needs foundation walls due to freezing winters. It’s just as imperative that any moisture or seepage that does get through be corrected in a manner that fits the site.

Great Work, Wrong Project

By Dave Hutcher

A real-world example in which a general contractor did good work on a foundation, but it wasn’t the work needed to fix the problem.

History of Drain Tiles

By Matthew Stock

A brief look at how drain tiles, which started in agricultural fields centuries ago, became common in building use.

Which System Is Better – TPO, EPDM, or PVC?

By Joel Lozon

Don’t just leave the decision about roofing to your roofing contractor. In two parts, we answer questions about roofing systems using TPO, EPDM, and PVC, and attempt to discern the basic differences between the three systems.

Making the Most of Digital Events

By Vanessa Salvia

Around the world, in-person events are no longer taking place. If you’re committing to attending the same events you used to, here’s how to make the most of them when they’re online.

Becoming a More Digital Friendly Business

By Vanessa Salvia

In today’s world, what customers want has changed. The general public has a new, high level of risk avoidance but businesses have an ongoing need to find new customers. Here’s how you can make changes to your waterproofing business to be more “digital friendly.”

Additional Info

Additional information

| Weight | N/A |

|---|---|

| Magazine Format | PDF Downloadable Magazine, Print Mailed Magazine |

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.